.jpg?environment=live)

ShareThis is disabled until you accept Social Networking cookies.

F1: Monza memories from the LAT archives

Autodromo Nazionale Monza is one of the last iconic Formula 1 tracks that still possesses its original character. Still superfast, despite the chicanes; still atmospheric, despite the gladiatorial element of F1 disappearing; still possessing a soul in a way that most of the tracks that remain on the calendar couldn't hope to emulate.

Strange, sometimes dramatic things happen at Monza, too, even if it's a dreary race, and these form our memories of being there, of watching the race on TV, or of reports we've read while delving through old books and magazines. Attending an Italian Grand Prix should be on everyone's bucket list.

So when, in the early summer of this year, we started hearing threatening noises regarding Monza's future on the F1 schedule, it truly felt like something sacrilegious was happening to the fabric of our sport. Daniel Ricciardo, who's won fans everywhere (except, perhaps, on the other side of the Red Bull Racing garage) earned further respect from oldtimers and youngsters alike when he stated: "Monza is one of the best weekends in terms of fans, atmosphere and passion. It's like Silverstone and Spa: some tracks on the calendar just need to stay there."

Ricciardo is just 25 years old, and he gets it. Let's hope there are people of similar mind, heart and soul in charge of the FIA's scheduling in years to come.

We shall dive into LAT's wonderful archives again for more Monza magic at a later date, but for now, we've covered a selection of years from the start of Formula 1's 3-liter era in 1966 to the end of the first turbo era in 1988. We're sure you'll enjoy…

The image at the top, incidentally, is from the classic 1971 Italian GP. Here, surprise winner Peter Gethin (BRM) holds off polesitter Chris Amon (Matra).

1966 - Scarlet fever

The beautiful Ferrari 312s of Ludovico Scarfiotti and Mike Parkes line up in pit lane before the start of practice. Parkes (BELOW) was underrated by many, but not by Scuderia Ferrari, who regarded him as a genius test driver. He took pole, but ultimately missed out on victory by just six seconds to his Italian teammate Scarfiotti (BOTTOM). "Lulu" was better known as a sportscar racer, and had shared the winning Ferrari at Le Mans in 1963 with compatriot Lorenzo Bandini, the winning Ferrari at Nurburgring 1000km with John Surtees in ’65, and was second in that glorious Ferrari 1-2-3 at the 1967 Daytona 24 Hours. Victory here at Monza would be his only F1 triumph, but not a bad one for an Italian to achieve…

1967 - The greatest at his greatest

Jimmy Clark was leading the Italian Grand Prix comfortably in his Lotus 49 Ford-Cosworth, when on the 12th lap, he suffered a puncture and lost a lap. He caught the back of the field and carved his way through to the front to unlap himself, generously towing new leader, his teammate Graham Hill, clear of the chasing pack. Clark then disappeared up the road…only to reappear in their mirrors. He'd made up a whole lap and, had sliced his way back into the lead by lap 60! Sadly, on the final lap, the Lotus's fuel pump failed to pick up the last dregs of fuel, allowing the battling John Surtees (Honda) and Jack Brabham (Brabham) ahead. Surtees crossed the line first with Brabham right behind him. But there has never been a greater third place in Formula 1 history.

Our pictures show (ABOVE) Clark leading Dan Gurney's glorious Eagle-Weslake in the early stages; (BELOW) Brabham courteously indicating to Clark on lap 12 that he has a deflating rear tire…

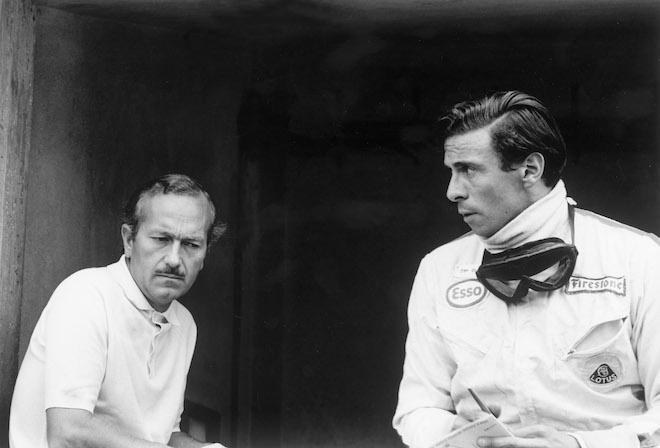

…(ABOVE) Lotus founder Colin Chapman and Clark with faces like they've just missed out on their greatest victory, but we suspect this was actually taken in practice…as was this picture (BELOW) of Enzo Ferrari making a rare trip to see his cars in action. Here he speaks with ace designer and engineer Mauro Forghieri. (BOTTOM) The pretty and victorious Honda RA300 of John Surtees, also nicknamed the Hondola, given that it was a Honda engine in an adaptation of a Lola Indy car chassis.

1970 - A fallen star and a rising hero

What a difference a day makes, as the song goes. On Saturday, Sept. 5, Jochen Rindt (ABOVE), championship leader, Lotus ace and possibly the fastest driver in Formula 1 at the time, crashed to his death when he hit the brakes and his wingless Lotus 72 veered off the track and into a guardrail at Parabolica. Here, he stands ready to head out with ace mechanic Eddie Dennis, as Chapman watches on.

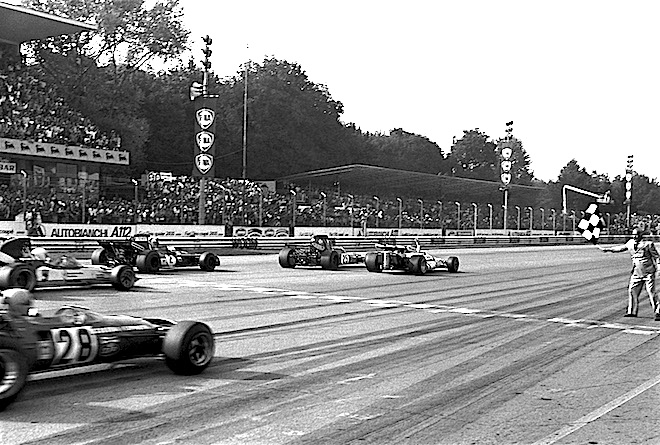

Come Sunday, there was a battle royal – a typical Monza slipstreamer – in which the lead changed hands almost 30 times, between the Ferraris of Jacky Ickx and Clay Regazzoni, the Tyrrell-run March of Jackie Stewart and the BRM of Pedro Rodriguez, seen leading (BELOW)…

…but it was eventually Regazzoni (BELOW) who prevailed, having broken the tow from the chasing pack, led by Stewart. Had Ickx and Regazzoni swapped cars, so that it was the Belgian ace who'd won, and Clay who'd retired with clutch problems, Ickx would have overhauled Rindt's points total by season's end. Instead, Rindt became Formula 1's only posthumous World Champion.

1971 - Five within one second

No, we couldn't leave out this classic, where Peter Gethin's BRM held off Ronnie Peterson's March, Francois Cevert's Tyrrell, Mike Hailwood's Surtees and Howden Ganley's BRM in a five-way drive to the line that saw them covered by just 0.61sec. There had been a similar slipstreaming thrash in 1969, but this one established a new record for the fastest F1 grand prix of all time, at an average of 150.754mph. The reason it would remain unbroken for 32 years is that by the ’72 Italian GP, chicanes had been installed, slowing the cars down and breaking up the slipstream packs.

(BELOW) Peter Gethin, a Briton already known by motorsport fans on this side of the Atlantic as the guy who finished third in the 1970 Can-Am Championship, looks slightly bemused by his success at Monza, and well he might - he never led a complete lap in F1, and yet still won a race…

…Chris Amon, by contrast, led several laps in his career (BELOW) and should really have been 1968 World Champion. But the polesitter for this ’71 Italian GP had typical "Amon Luck" while fighting for the lead. He reached up to remove a tear-off strip from his visor, and the whole visor came away in his hands. Inevitably blinded by the 190mph slipstreaming, he fell half a minute behind the winner, in sixth. (BOTTOM) Peterson's March battles with Hailwood's Surtees. They would ultimately finish second and fourth, respectively. This was one of four runner-up finishes for Peterson in ’71, enabling him to finish a distant second behind Jackie Stewart in the points table.

1974 - Ronnie repeats

Remember we mentioned strange things happen at Monza? Ronnie Peterson was a prime example. In 1971, he finished second to a guy who, as we mentioned, never led a complete lap of a grand prix. In ’73, he won, just ahead of his teammate Emerson Fittipaldi, thereby ensuring the title went not to Emmo but to Tyrrell's Jackie Stewart. In ’74, Peterson won again, just ahead of Fittipaldi (ABOVE) who by now was at McLaren and heading for World Championship No. 2. In ’76, he won again…this time for low-budget March. And in ’78, it was Monza where he crashed, leading to the urgent operation which ultimately cost him his life.

Monza was also the place where he was seen in public for the final time in the troublesome Lotus 76 (BELOW), during practice, but it was a second a lap slower than its 5-year-old (!) predecessor, so his decision to stick with the 72 was an easy one to make....and it paid off.

(ABOVE) Closest opposition to the Peterson/Fittipaldi battle was Jody Scheckter in the Tyrrell 007, but that was hardly a surprise, as two wins and regular points finishes meant Jody finished third in the championship, only 10 points off the top. What was an utter shock, however, was the performance of Arturo Merzario in the Frank Williams-entered Iso Marlboro FW04 (BELOW), which finished fourth. This picture was taken in practice, as the Mike Wilds-driven Ensign that trails in this picture failed to qualify for the race.

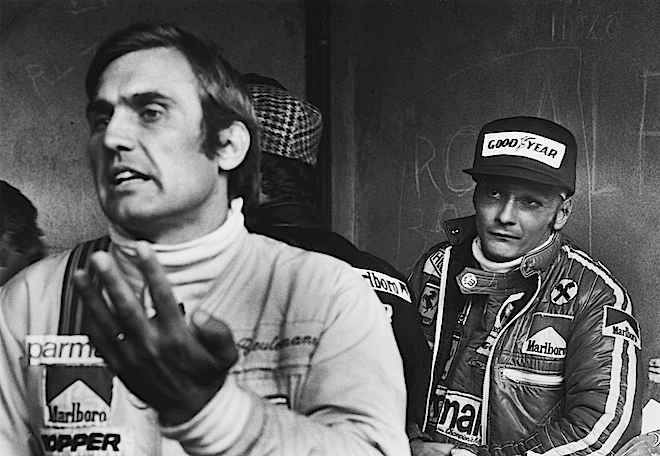

1976 - The miracle

If anyone can explain how a guy given his last rites 33 days earlier and still in agony from severe burns to both his face and his lungs can get back into a Formula 1 car and perform so strongly, that person can only be Niki Lauda. In practice he got nervous when it first started raining – who knows? maybe delayed shock. But then he got his head in gear, and drove fast enough to eclipse his two teammates in qualifying. Two? Yeah, Ferrari had hired Carlos Reutemann (who'd partner Lauda full-time in ’77) for the weekend as a back-up, should Lauda not be back to his best. Niki's enthusiasm for the idea is written all over his wounded face (BELOW). Although Regazzoni, his other teammate, got ahead of him on race day and finished second, Lauda's fourth place was as brave a drive as anyone had seen, and he finished five places and almost 40sec ahead of Reutemann…

In the mean time, James Hunt, who'd been made to start at the back of the grid because he was racing in Italy and was main title rival to a Ferrari driver because of fuel irregularities, spun out, to the delight of the tifosi. His walk back to the pits (BELOW) past the jeering crowd was not without its perils, as you'd imagine. Meanwhile, Ronnie Peterson conquered all the big teams with his March (BOTTOM) and scored his third Monza win in four years. It would be March's final F1 victory.

1979 - The tifosi's dream result

Ferrari's Jody Scheckter arrived at the Italian Grand Prix needing only four points to clinch the World Championship, at a time when points were distributed 9-6-4-3-2-1 to the top six. When the turbocharged Renaults of Jean-Pierre Jabouille and Rene Arnoux on the front row fouled up their start, Scheckter jumped into the lead (ABOVE), with teammate Gilles Villeneuve slotting into third. Arnoux whistled past the leader on the second lap, but when his Renault expired, Ferrari had itself a 1-2 and team orders were that whoever was ahead on assuming a that situation would stay ahead. Villeneuve dutifully followed his team leader to the checkered flag, finishing half a second behind the new World Champion, having earlier staved off the advances of Jacques Laffite's Ligier (tucked in behind, BELOW).

When Laffite (one of Scheckter's few opponents for the crown) and the second Renault of Jabouille retired, Clay Regazzoni, now in the superior Williams FW07 (BOTTOM) closed down the Ferraris but came up five seconds short.

1982 - A ray of light

Mario Andretti, who thought he'd retired, got the call from Maranello. A hero had never been more desperately needed. Gilles Villeneuve had crashed to his death in Zolder, Didier Pironi had shattered his legs at Hockenheim and would never race again. Villeneuve's replacement, his good friend Patrick Tambay, had won that German race, but he couldn't carry the team's hopes alone. The B-spec version of the Ferrari 126C2 was proving an excellent car, and one worthy of the Constructors' Championship, but to clinch that, two cars were necessary.

The 1977 Monza winner, who had been racing Indy cars that season for Pat Patrick, had no hesitation in accepting Ferrari's offer, flew into Italy to great fanfare, tested for a day at Fiorano and set a new track record, and then rested his mechanics. Come practice time, he re-learned about setting hot laps with other cars on track, discovered all he needed to know about the turbo lag and the power band of this peaky 1.5-liter V6, whose delivery differed greatly from the 2.65-liter V8 turbos in CART Indy cars. And on Saturday, he beat Tambay, the Brabham BMWs of Nelson Piquet and Riccardo Patrese and the Renaults of Alain Prost and Rene Arnoux to pole. Even to hardened journalists, this remains one of the happiest days in Monza's history.

Come the race, a sticky throttle that exacerbated the turbo lag characteristics relegated him to third behind Arnoux (BELOW) and Tambay, but with Rene having recently announced he'd be joining Ferrari for 1983, the tifosi felt able to celebrate the perfect podium (BOTTOM) – a Ferrari 1-2-3!

1988 - Honoring Enzo

Somewhere up there are two Ferrari drivers (and a Rome-born American!) who have stunned the racing world and sent the local crowd into raptures. Finally, in a season of McLaren-Honda domination, the scarlet cars have triumphed, and less than a month after Enzo Ferrari's death, at the age of 90.

Gerhard Berger and Michele Alboreto needed help, of course – the MP4/4 was light years away from an updated F187, in both speed and fuel mileage. Berger and Alboreto had qualified 0.7sec and 1sec behind the pole-sitting McLaren of Ayrton Senna, and their inability to make it to the end of races without winding down the boost had become legendary. That's why, despite having some 100hp more than the best normally-aspirated cars, the Ferraris were often also beaten by the Benetton-Fords that season.

The aid that came Ferrari's way at Monza came from a couple of Frenchmen. The first was Alain Prost, whose Honda engine had a misfire in the early stages which became a lapse onto seven cylinders. Yet, knowing his car was therefore unlikely to make the finish, he turned up the boost to maximum to compensate for the misfire, and closed in on teammate Senna. His championship rival responded in the manner Prost hoped he would – by speeding up, using up his own juice quicker than was prudent at a race which was tricky to complete on only 150 liters.

Sure enough Prost's engine let go with 16 laps left to run but he'd done the damage he'd intended. In the closing laps, Senna was low on gas, and trying to keep Berger and Alboreto at arm's length, which meant not losing momentum behind backmarkers. Into the first chicane on the penultimate lap, he dived inside the Williams of Jean-Louis Schlesser, who that weekend was making his Grand Prix debut (just a day away from his 40th birthday!), subbing for the unwell Nigel Mansell. Sauber's French ace in the World SportsCar championship made room but slid wide on the dirty line, half into the sand. As the Williams regained the track, Senna's McLaren claimed precisely the piece of pavement Schlesser needed. The pair made contact, and the red and white car was looped into a spin and was left beached on a curb.

The tifosi expressed its sympathy for Senna in predictable fashion, as Berger and Alboreto flashed by to score a 1-2 finish, ahead of an Arrows 3-4, for Eddie Cheever and Derek Warwick. It was the perfect result at the perfect venue at almost the perfect moment in Ferrari's history. If only the Old Man had lived just one month longer…

(BELOW) Gerhard Berger on his way to breaking the McLaren monopoly; (MIDDLE) Jean-Louis Schlesser, the French driver of a Swiss-German sportscar and a British F1 car who became an accidental hero to every Italian racing fan; (BOTTOM) Michele Alboreto, who finished his final Italian GP for the Scuderia with a second place and fastest lap.

Topics

ShareThis is disabled until you accept Social Networking cookies.

Latest News

Comments

Disqus is disabled until you accept Social Networking cookies.